Over the millennia First Nation people in the Yukon lived a nomadic lifestyle. They followed the game and moved with the seasons to different locations where sources of food were known to be. Although life was simple it was by no means easy. Elders tell us stories of starvation, when our ancestors couldn’t find enough nourishment to sustain the group and many people perished. Despite the harshness of the environment they were able to persevere and survive.

Fact and Legend

Scientists and archaeologists also have a story to tell in the Yukon. Their story is similar to ours and often correlates scientific fact to legend. They say that man was first evident in the Yukon about 15,000 years ago after our ancestors migrated over the land bridge known as Beringia which, during the last ice age, was a massive steppe connecting Siberia and Alaska. They slowly migrated into North America and the people who are now known as Yukon First Nations were part of some of the last waves of people to cross the land bridge.

During this time the Yukon was also home to many animals who have gone extinct since then. Woolly mammoths, giant beavers, and giant bears are present in the stories during a time when animals and humans were interchangeable and the world around us was not as we see it today. Over thousands of years the people in the Yukon settled into their traditional territories and developed distinct languages and cultures, and this is how we define our various groupings today.

Languages

There are eight language groupings amongst Yukon First Nations. There are two major language families: Athabaskan and Inland Tlingit. Athabaskan is further subdivided into seven dialects of Athabaskan which are: Gwich’in, Hän or Tr’ondek Hwech’in, Upper Tanana, Northern and Southern Tutchone, Tagish and Kaska. The Athabaskan language family extends over an immense area of North America and is the largest language family. The Tlingit people and language originate from Southeast Alaska and they made their way into the Yukon at least 300 years ago to trade with the people of the Interior, the Athabaskans. Many of our people in the Southern areas have both Athabaskan and Tlingit ancestry.

There are eight language groupings amongst Yukon First Nations. There are two major language families: Athabaskan and Inland Tlingit. Athabaskan is further subdivided into seven dialects of Athabaskan which are: Gwich’in, Hän or Tr’ondek Hwech’in, Upper Tanana, Northern and Southern Tutchone, Tagish and Kaska. The Athabaskan language family extends over an immense area of North America and is the largest language family. The Tlingit people and language originate from Southeast Alaska and they made their way into the Yukon at least 300 years ago to trade with the people of the Interior, the Athabaskans. Many of our people in the Southern areas have both Athabaskan and Tlingit ancestry.

A Time of Change

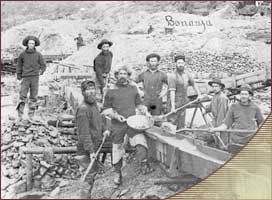

The 19th century was a time of change in the Yukon. Previous to this, our people encountered the occasional explorer, fur trader and missionary but nothing compared to the impact felt when the Gold Rush of 1898 occurred in the Klondike, the homelands of the Tr’ondek Hwech’in. Forty thousand white prospectors swooped into the Yukon during the Gold Rush, all seeking the opportunity to strike it rich. They made their way from the southern Yukon through Tagish, Southern Tutchone, Northern Tutchone and Tr’ondek Hwech’in territories. Life was never the same again for Yukon First Nations and they learned to adapt and change in order to survive in this new way of life. When the gold seekers left, the Yukon was left alone and was of no interest to anyone other than our people until the next great force of change, known as World War II occurred.

The 19th century was a time of change in the Yukon. Previous to this, our people encountered the occasional explorer, fur trader and missionary but nothing compared to the impact felt when the Gold Rush of 1898 occurred in the Klondike, the homelands of the Tr’ondek Hwech’in. Forty thousand white prospectors swooped into the Yukon during the Gold Rush, all seeking the opportunity to strike it rich. They made their way from the southern Yukon through Tagish, Southern Tutchone, Northern Tutchone and Tr’ondek Hwech’in territories. Life was never the same again for Yukon First Nations and they learned to adapt and change in order to survive in this new way of life. When the gold seekers left, the Yukon was left alone and was of no interest to anyone other than our people until the next great force of change, known as World War II occurred.

Alaska Highway

Yukon First Nations were aware of the War. They heard the reports on the radio and read about it in magazines.They truly had no idea how great an impact WWII would have on their lives after this great world event. In 1942 the Americans built the Alaska Highway connecting Alaska to the rest of the Continental United States. Our Grandfathers were hired as guides to show the soldiers the best routes. Much of the highway exists on those old trails used by our people to travel by foot or by dogteam. The highway brought twelve thousand American soldiers with their heavy equipment and tent cities into our villages and the town of Whitehorse.

Yukon First Nations were aware of the War. They heard the reports on the radio and read about it in magazines.They truly had no idea how great an impact WWII would have on their lives after this great world event. In 1942 the Americans built the Alaska Highway connecting Alaska to the rest of the Continental United States. Our Grandfathers were hired as guides to show the soldiers the best routes. Much of the highway exists on those old trails used by our people to travel by foot or by dogteam. The highway brought twelve thousand American soldiers with their heavy equipment and tent cities into our villages and the town of Whitehorse.

The sudden changes were shocking and difficult to adjust to because of the hastiness of their arrival. The soldiers brought diseases which soon evolved into epidemics; influenza, whooping cough, dysentery, and Tuberculosis wiped out an estimated 50 percent of the population from the time of initial contact to the time of the highway. New, permanent towns sprung up along the highway and the old way of nomadism was gone forever. The people left their trap lines because shortly after the war the price of furs dropped drastically and this vital economic base line was gone. At this time, the Government allowed First Nation people to enter alcohol establishments and so began a tempestuous battle with alcoholism as the people had no tolerance to its devastating effects.

Mission Schools

By this time Yukon First Nations were still considered wards of the state and governed by the Federal Department of Indian Affairs. In addition, many mission schools were in operation. The largest ones; the Catholic Church in Lower Post, B.C and the Chootla Anglican School in Carcross saw three generations of Yukon First Nations come through their doors. It was the law that Status Indians send their children to the Mission Schools and this was enforced by the R.C.M.P. Children from as far away as Old Crow were sent to Carcross where they remained for 10 years or so, without seeing their families. The mission schools were set out by the Federal Government who were heavily involved with their policy of assimilation, which sought to turn Canada’s First Nations into that of mainstream society. The schools did a very good job in accomplishing their purpose: stripping the children of their dignity, their identity, and their familial and communal ties. However, despite verbal, emotional and sometimes sexual abuse, our people survived.

By this time Yukon First Nations were still considered wards of the state and governed by the Federal Department of Indian Affairs. In addition, many mission schools were in operation. The largest ones; the Catholic Church in Lower Post, B.C and the Chootla Anglican School in Carcross saw three generations of Yukon First Nations come through their doors. It was the law that Status Indians send their children to the Mission Schools and this was enforced by the R.C.M.P. Children from as far away as Old Crow were sent to Carcross where they remained for 10 years or so, without seeing their families. The mission schools were set out by the Federal Government who were heavily involved with their policy of assimilation, which sought to turn Canada’s First Nations into that of mainstream society. The schools did a very good job in accomplishing their purpose: stripping the children of their dignity, their identity, and their familial and communal ties. However, despite verbal, emotional and sometimes sexual abuse, our people survived.

In 1960, First Nation people in Canada were given the right to vote for the very first time. This brought unparalleled hope to Yukon Indians. A new generation emerged, barely intact from the brutality of the mission schools, and began a movement to fight oppression, provide vision and hope, and to gain some rights for the generations to come.